Fisheries 2027 Consultation – SACN Response

We are grateful for the opportunity to input to the DEFRA vision for the future of Marine Fisheries.

The Sea Anglers Conservation Network has members throughout the British Isles, and a few beyond. Steadily growing, we have over 500 lines of membership, a number of them being angling organisations clubs and federations extending our reach to many thousands of anglers. Our membership is largely drawn from the ‘internet community’ and especially those anglers who have an interest in conservation of our marine resources and the future development of the Recreational Sea Angling sector, and the UK’s Recreational Sea Fisheries.

Please find our detailed response to the consultation attached.

Regards,

Leon Roskilly

Sea Anglers Conservation Network

Vision 2027 – Recreational Sea Fisheries and the Recreational Sea Angling Sector

Vision Statement

1. As the result of a successful DEFRA RSA Development Strategy, supported by a cross section of key marine stakeholders, there will be a greater participation in Recreational Sea Angling, providing increased Social and Economic returns to UK PLC.

• Between three and four million anglers will regularly fish in the sea, directly spending over £2 billion pounds and supporting around 80,000 livelihoods, mostly in small businesses servicing the sector.

• There will be a local fleet of angling charter boats operating from almost every harbour, with tackle shops supplying bait and tackle to the Recreational Sea Angling Community in most coastal locations.

• As well as an increase in the number of people participating in Recreational Sea Angling, the average number of trips per angler will have quadrupled from a base established in the early 2000’s, and anglers will be spending a significantly greater proportion of income on first class tackle and angling trips.

2. Recreational Sea Anglers will have access to more and bigger fish

• There will be real prospects that national size records for major RSA species will be repeatedly broken (although this is happening now with freshwater species, partly through better fish growth owing to improved environmental conditions for some species, and partly through improved tackle and angling techniques, sea fish records established before growth overfishing are not even approached nowadays)

• Regional, Venue, and Club records will be broken regularly.

• There will be keen competition for specimen trophies for all species, with many entries being received.

• All anglers will have good prospects of catching within any particular year, fish of a stamp that would have been regarded as a fish of a lifetime in the early 2000’s.

• Young and inexperienced anglers will have access to close to shore fishing opportunities where reasonable catches can be made without the need for a high level of skill, or investment in high quality tackle.

3. The United Kingdom will have the reputation of containing world class Recreational Sea Fisheries.

• Proportionately fewer UK anglers will be travelling overseas for exceptional fishing opportunities, whereas increasing numbers of continental anglers will be visiting the UK to sample and take back experiences of well managed Recreational Sea Fisheries, with very real implications for lessening of carbon emissions due to long distance flying.

• Journalists, economists, scientists and social scientists will be studying the restoration of UK Recreational Sea Fisheries as an example to be followed world-wide.

4. UK anglers will have unparalleled access to fishing opportunities.

• New coastal structures and installations (marinas, piers, docks etc) will incorporate access facilities for anglers.

• Rights of access by Recreational Sea Anglers will be established on existing structures and installations

• Structures will be provided specifically for angling access where these will provide exceptional regional fishing opportunities from the shore.

• All access will be designed with the needs of disabled and young anglers in mind and with regard both to angler safety and easy access to fish and the landing of fish (ie safety barriers can sometimes make landing of fish difficult and fishing uncomfortable, floating pontoons, close to the water at all stages of the tide, are often a better option than stilted structures).

• There will be reasonably priced boat launching facilities within easy reach of most popular fishing marks, and safe car parking available within a reasonable distance of angling facilities.

• Anglers access to the foreshore will be safeguarded

• Particularly in estuaries and popular angling marks, and in most of the area covered by the Golden Mile, commercial fishing operations that interfere with anglers’ enjoyment, or remove stocks of species of interest to anglers, will be curtailed.

5. There will be adequate finance available, both for the development of the RSA sector and for businesses that service the sector, and for organisations concerned with the development and protection of the sectors interests.

• Along with funding of other sports, organisations that provide coaching and competition opportunities for Recreational Sea Anglers will be properly funded by Sports England.

• Infrastructure facilities that support the development of Recreational Sea Angling; angling structures and access, facilities used by angling charter boats, development of reefs and other fish aggregation areas with access for anglers etc., will receive the same consideration when applying for EU and UK development funding as commercial fishing infrastructure currently enjoys.

6. Anglers will be aware of restrictions, and their responsibilities towards the environment.

• At popular angling places, and in local tackle shops, there will be clear signposting of restrictions such as minimum landing sizes, rights and restrictions of other contending users within the area (jet-skis, netting etc), codes of conduct to be observed by anglers, and other information of interest (such as consultations and proposed byelaws etc). Such information will be available to individuals on developing technologies.

• There will be incentives for anglers to join clubs (such as preferential access, lower costs etc), and clubs will be given incentives to communicate information to individual members.

• In view of the much greater increase in angler participation, there will be restrictions on bait collection where this has significant environmental impacts, but increased investment in bait production and aquaculture will both increase the availability of bait, and reduce its cost.

• Some restrictions will be required in some areas for some species of fin-fish, but these will be proportionate to the risk across all stakeholders that remove fish of those species, with particular regard to socio-economic return from capture of those species by different methods, and the need to maintain the viability of RSA infrastructure (angling charter fleets etc).

7. There will be regularly updated data on the performance and impact of the Recreational Sea Angling Sector, and science undertaken targeted at understanding the species of value to RSA, as well as the sector’s social and economic performance.

• Key Recreational Species will have been identified and species management plans put into operation and subject to performance review..

• There will be an established science programme looking at stock structure of species of interest to RSA, interactions of those species with the wider ecology of the marine environment.

• There will be various schemes for recording anglers’ catch data, monitoring trends in availability and size of fish targeted and caught.

• There will be regular reviews of the social and economic performance of the sector with the objective of maximising the growth of the benefits provided by the sector in an environmentally responsible framework.

8. Participation in Recreational Sea Angling will be encouraged.

• Acknowledging the value of the Recreational Sea Angling Experience in bringing citizens into intimate contact with the marine and coastal environments, particularly in providing young people with a worthwhile open air pursuit, there will be facilities within schools and other institutions guiding young people to provide information about the benefits of participation in RSA, together with opportunities for coaching and organised trips.

• RSA coaching and guiding facilities will be accessible to most of the population.

• Acknowledging the suitability of RSA as an activity that can be engaged in by people with a wide range of disability, facilities for disabled people to learn and practice RSA will be positively encouraged.

9. Angler Participation

• Anglers will be encouraged and given incentives to join local clubs and regional and national organisations to ensure an infrastructure which can collate and collect data about RSA participation, catches and local and regional recreational fishery issues, and aid scientific examination of factors affecting and being affected by RSA.

• Anglers and angling organisations will be given incentives and encouraged to, and will participate effectively, in bodies that regulate, manage and develop and protect both recreational sea fisheries and the wider marine ecology

10. Recreational Fishery Managers

• Organisations that manage Recreational Sea Fisheries will have an intimate understanding of the needs of the RSA sector, and will work to deliver the best RSA experience possible.

• They will have effective RSA representation on bodies where appropriate.

• They will consult with Recreational Sea Anglers at all levels, both with RSA organisations and proactively with individual anglers.

• They will have the correct management tools, and resources, to enable them to develop world class Recreational Sea Fisheries within the UK.

• They will have specific legal duties towards the establishment of and development of Recreational Sea Fisheries wherever it is possible to do so.

Specific Questions asked by DEFRA:

How much access to fisheries should be available for recreational angling?

It is generally acknowledged that Recreational Sea Angling is socially important.

It provides a means of relaxation for many of its participants, reducing the effects of the stress of modern life.

It introduces many people to the beauty and complexity of the marine environment and ecology in an active and intimate way, increasing understanding of that environment and increasing the awareness of the value of that environment.

It provides the opportunity for open air activity for many young people, and a distraction from less desirable pursuits.

It is accessible to most disabled people and to all other groups, and through club activity and pursuit of sport produces a cohesive benefit for wider society.

The economic importance of Recreational Sea Angling is substantial

A number of recent studies have confirmed not only the current economic importance of RSA, but also its considerable development potential.

Evidence from restored Recreational Sea Fisheries overseas shows that when the abundance of fish available to Recreational Sea Anglers increases and, importantly, when the stamp of fish being caught significantly increases, not only do anglers make more trips, but they are more likely to be joined by colleagues, friends and relatives, and with a better quality of experience available, participants spending increases as they invest in better more modern tackle and boats, and are prepared to travel further and spend more on productive trips when the quality of fishing available is improved.

There is evidence that many anglers are now travelling overseas seeking better angling experiences than are currently available in the United Kingdom, and that UK RSA businesses are investing in and relocating to angling destinations outside of the UK. (This very much contravenes the argument of some that anglers will simply switch to (say) golf and there is no economic impact from a decrease in angling activity caused be declining opportunity in the UK.

If the UK Recreational Sea Fisheries are restored, then there is little doubt that a far greater proportion of anglers’ spend will take place in the UK, as well as a much increased number of trips to the UK by continental anglers, often bringing families for a holiday here.

The RSA sector currently supports over 19,000 livelihoods, angling guides and coaches, angling charter boats, bait-diggers, bait suppliers, tackle manufacturers, suppliers and local tackle shops etc. The number of livelihoods supported and the availability of business opportunities in the sector are capable of being substantially increased.

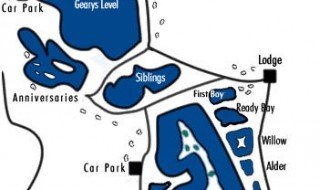

Most Recreational Sea Angling takes place in a limited area

Most RSA activity is shore based, with catches restricted to fish swimming in casting range of beaches and piers and similar structures, often no more than 100 metres out, and never more than 300 yards.

Small angling boats are generally restricted to estuaries and sheltered waters.

The angling experience could therefore be boosted considerably by increasing fish availability in a comparatively small area of the sea, often referred to as the ‘Golden Mile’, especially along areas of the coastline favoured by anglers, and around inshore wrecks and reefs.

Recreational Sea Anglers rely on relatively few fish of commercial importance.

When attempting to compare the relative values of both the catching sector and the Recreational Angling sector, it is important to realise that much of the value of the catching sector comes from species of no direct interest to Recreational Sea Anglers.

Certainly shellfish and crustaceans.

Certainly many species of fish not generally available to Recreational Sea Anglers, blue whiting, monkfish etc

And many of the fish targeted by Recreational Sea Anglers is of little importance to the commercial fishing industry; mullet, wrasse, flounder, tope to name but a few

Given the considerable economic and social benefits that are derived from Recreational Sea Angling, and the sectors potential for increased development and participation, there is a considerable amount to be gained in substantially increasing priority angler access to close inshore areas and a number of species of fin fish, as well as boosting stocks that are of common interest to both Recreational Sea Anglers and the catching sector, and by ensuring that all access by all those who remove fish from the environment is well regulated and undertaken on a precautionary basis with stock policies suited to the need of the RSA sector (big fish as well as many fish!)

Does it matter how much of the fish we eat is from aquaculture?

One of the reasons used for promoting aquaculture is the growing inability to source fish from diminished wild stocks owing in the main to ‘uncontrollable’ over-fishing.

If wild fish stocks were well managed and restored to more traditional levels, much of the market for aquaculture would be considerably reduced.

Therefore it would be wrong to plan for a 20 year vision that assumes restoration of fish stocks and which also sees the continued strong development and growth of aquaculture.

Rather planning should seek to reduce the need for reliance on the output from aquaculture.

Aquaculture brings its own well documented problems; reliance on further diminishing wild stocks (and the food of wild stocks) to fulfil the demands of feeding farmed fish; chemicals and waste discharged into the marine environment to the detriment of the surrounding ecosystem; risks of escaped fish competing with wild-stocks and the introduction to wild stocks of genetic changes that are undesirable and damaging in wild populations; driving up the costs of other food production industries reliant on the same sources of feed.

Even as an industry which has the role of supplementing full capacity of wild fish stocks, extreme care should be taken to ensure that obtaining inputs such as feed has no negative impacts on wild fish stocks and the wider marine ecology, and that outputs are fully contained within the operation or disposed of in an environmentally acceptable fashion.

Although much progress has been made in ‘cleaning up the act’ of aquaculture operations, there is still too many negatives and unacceptable risks to countenance anything other than minimal reliance on aquaculture, with the bulk of investment and development effort being concentrated on restoring wild fish stocks rather than hastening their destruction to increase the profits of operations that seek to reduce reliance on diminishing stocks.

By 2027, there should be little reliance on aquaculture to source fish products as replacement for diminished wild fish stocks, and where there is a place for aquaculture, it should be positioned to be regarded as a ‘clean’ sector.

We need to avoid building a sector that potentially introduces as many problems as it solves, on the back of a temporary diminishment of wild fish stocks that we intend to fix.

It would be unfortunate if we are then left with an established aquaculture sector that is no longer needed at such a size, but fights to maintain its no longer justifiable existence, competing with and perhaps reducing the need to restore the products of the wild fishery.

What is an acceptable level of environmental impact for different parts of the supply chain?

Marine ecosystems are under increasing threat.

As systems are progressively damaged and resources diminished we must constantly review the criteria needed to adequately protect, and to allow the restoration, of what is currently available.

Practices that have been within ‘acceptable limits’ in different times, may now be entirely unsustainable.

Unfortunately, there is always a cultural lag and a disbelief that long established and traditional practices now need to be regarded in a different light.

And it is this disbelief, and lag in understanding that fundamental changes have occurred, which is often responsible for preventing the acceptance of restraints that would otherwise prevent each step towards a predictable disaster.

Wherever we are inclined to draw the ‘acceptable’ line today, will not apply to the conditions we find tomorrow.

It is undeniable that (apart from a few arguable instances) the general direction of the health of our marine resources are in decline, and therefore the acceptable level of environmental impact is increasingly higher in response.

And so many wish that it had been set higher in the past, so that it need not be set so high now.

We must now decide where to set that acceptable level now, knowing from past experience that failure to set it high enough now will only mean an increased level of pain to be endured in the future.

In simplistic terms, the acceptable level of environmental impact today must be one that not only doesn’t risk further damage to a degraded environment, but also allows the real possibility of recovery and restoration.

Defining an ‘acceptable level’ in political terms is an altogether different and more difficult problem, and yet one that must be firmly addressed if future prosperity (economic, social and environmental) is to have any part in this 20 year vision.

How much access to fisheries should be available to coastal communities through Government intervention?

Anyone familiar with ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, and with the history of the worldwide disaster that we call ‘fisheries management’ would rightly recoil in disbelief that there should be a suggestion that fisheries management should be left entirely to ‘the market’s operation’

Systems whereby individual exploiters are given ownership of a share of the resources available, and profit from an increasing value of that share (or at least maintenance of the value of the resource at its optimum level), show some promise.

But this requires at least some Government intervention to set up such schemes that incentivise exploiters to maintain the future value of the resource. (And in considering ownership of such shares, other factors than simply economic benefit must be proportionately considered, including social values and the rights of communities).

It needs to be understood that our marine resources are the common property of all the people of the UK, and as a people each of us has a stake in how well those resources are managed, even if the only benefit is the national pride that comes from knowing that our nation values and applies principles of good husbandry that will maintain our natural national wealth for this and for future generations.

And so it is extremely important that the government, acting for the people, intervenes appropriately in the management of our marine resources, and resists the temptation to hand them to the most economically efficient operators.

What Information do consumers need to be able to make sustainable choices?

The impact of individual purchases of fish from wild stocks is extremely complex and most consumers need some kind of guidance at the point of purchase, delivered as simply as possible but with more information available to the more sophisticated and informed consumers.

A single trusted system, such as the Marine Stewardship Council’s symbol, perhaps with a ‘traffic light system’ of red, amber, and green is the minimum required.

What is NOT needed is a confusing array of schemes, some merely marketing ploys, to convey the impression that consumers are being offered a responsible choice.

And here the Government needs to back a scheme that has the wholehearted acceptance and support of all stakeholders, and to be responsible for ensuring that the fish consuming public is educated and aware of the value of that scheme.

And given modern technology, and the increasing need to monitor the entire supply chain, future consumers should be able to ask for information by which they can, if they so wish, trace the origin of their fish back to the fishing boat that caught it, where it was caught, the method used etc.

Is this a vision that you would endorse?

No, it fails to proportionately take into account the management of the UK’s Recreational Sea Fisheries.

Is the balance right between economic, social and environmental aspects?

No, see details given elsewhere within this response.

What if anything is missing?

A proper and proportionate appreciation of the development potential of the UK’s Recreational Sea Fisheries

Have we got the roles and responsibilities right?

Broadly yes

Have we identified costs and benefits correctly?

We feel that in places far too little emphasise has been given to societal values, environmental concerns, and to correcting the current direction and velocity of where fisheries management has been heading in preceding decades.

Which bits do you agree or disagree with?

Covered elsewhere.

General Commentary on the contents of the Discussion Document and other comments.

– Lack of Appreciation of the development Potential of the UK’s Recreational Sea Fisheries

Although Recreational Sea Angling is mentioned a number of times within the document, there is little specific detail as to DEFRA’s vision of how this now neglected sector could be developed considerably, increasing the social and economic value to be attained several times over, and at minimum environmental cost.

There seems to be little understanding that development of successful Recreational Sea Fisheries demands a fundamentally different management approach to that which concentrates purely on the development of harvestable stocks.

Development of Recreational Sea Fisheries involves concentrating some effort on management of species different to those of value to the catching sector and management of stock structure that allows for a more natural (and ecologically efficient) age and size range within the stock of particular species (which also ensures a more robust stock overall, with far less variability and uncertainty).

And given that the majority of RSA activity takes place within close inshore waters (ie involves only a tiny percentage of the entire spatial fishery area), and that much of RSA effort is directed at species of little commercial value, contention with other stakeholders that would potentially arise would be minor in relation to the benefits to be gained.

Used to dealing with a deteriorating situation where any growth is likely to cause more problems than solved, and by default a fisheries management that has focussed upon managing decline, it would seem that there is a cultural inability of fisheries managers to grasp the concept of development potential, otherwise the development of the RSA sector would be a star ingredient of any future vision at any timescale.

It is disappointing to see that vision ignored yet again in a document produced by DEFRA that aims to be a beacon pointing towards a better future for the UK’s fisheries.

– There will be rights of access to fisheries coupled with clear responsibilities

Fishermen will be fairly rewarded for fishing in the most ‘environmentally friendly’ way, especially when developing and using methods and gear to ameliorate damage to stocks and the marine environment above those strictly required, and for maintaining an excellent compliance record.

Fisheries that are most environmentally sensitive, but not necessarily most economically efficient, will be supported.

– Economically efficient commercial operators

The phrase ‘economically efficient commercial operators will have access to most of the resource’ has caused concern.

To judge which operators are most economically efficient means firstly defining the ‘bottom line’.

If that ‘bottom line’ is merely the value of the catch, then it is unfairly weighted towards a single operator.

If however it encompasses a wider value (ie the cost of infrastructure, business and employment opportunities, the maintenance of ecosystems etc), then the most ‘economically efficient operator’ is likely to be very different.

There is a tendency for capitalism to reduce real wealth; the richness of the environment; how good a population feels about itself; the satisfaction of the potential needs of future generations; the ‘services’ provided to mankind by a diverse ecology, into a single expression of wealth, ultimately meaningless figures on a bank statement.

And phrases such as ‘economically efficient commercial operators will have access to most of the resource’ are the tools used to take away such real assets from the true stakeholders and deliver them to others in order to simply inflate those ultimately meaningless figures.

A different approach is likely to lead to a much better and safer outcome for the greater majority, and for future generations.

– Economic Returns will be Maximised

‘In most cases fish stocks and access to use them, either commercially or recreationally, will be managed to maximise the economic return to society’

Involvement of social scientists, as well as economists, in the production of DEFRA’s vision is needed to produce a properly balanced vision.

The ‘social value’ attainable from the way that marine and fisheries resources are managed can be greater than the economic value and failure of the vision document to fully recognise this is a considerable weakness that undermines the likelihood of the achievement of many of the objectives stated throughout the document.

Attaining maximum value from lowest mortality

In the past fishermen have ‘grabbed and landed’ whatever is available assuming that any value attained is better than nothing.

Such an approach may be acceptable if this is not deemed to be environmentally damaging, but it never was the best way of attaining greatest value from fishing activity.

Rather than concentrating on quantity, management of likely returns is probably a better approach towards both economic and biological sustainability of both the industry and the resource that the industry needs to exploit.

• Avoidance of oversupply of markets to attain best price (and co-operating within the fleet to attain best price for all landings, rather than competing to be first to land etc

• Ensuring quality of landings, rather than quantity

• Harvesting at a size that returns maximum value, rather than grabbing barely legal sized fish before someone else does (again requiring co-operation between fishermen and fishing communities, including those from other EU countries to ensure that stocks are harvested to maximise value and sustainability is preserved – again ownership of shares in the overall stock value, rather than allowing ‘the tragedy of the commons’ to prevail is a possible solution.

• Where spawning aggregations are targeted, they should be targeted after spawning rather than before spawning, usually just as efficiently but at risk that they will be taken by someone else first. Some form of management is needed.

Reducing reliance on products from the Marine Environment

There was a time when the seas resources were deemed inexhaustible.

(Many of our current problems are as a result of our inability to shed attitudes established in the time that was believed to be true).

With marine products available, it has been natural that innovative markets be developed into which to deliver those products, increasing overriding reliance upon their availability.

(It is interesting to find the pig-farming industry now threatened by the need of the aquaculture industry’s growing and competing need for fish-meal).

Now that the limits of the capacity of the marine ecosystem to deliver such products has been exceeded, it is necessary to pro-actively find alternatives to marine products to satisfy the demand that was originally created by the assumption that marine resources were inexhaustible, rather than simply relying upon the market to find solutions.

Such research into decreasing mankind’s reliance on the products of the marine environment is as important as any research being carried out to understand the limits of exploitation of those resources in creating a world where the marine environment can flourish to serve future generations in so many ways.

Reducing reliance on our marine resources must also be an important component of any future vision of our ability to manage those resources in a wholly sustainable way.

– Benefits and Costs

– Social

• Development of the RSA sector will increase considerably the number of people who have an intimate interest in, and understanding of, the function and diversity of the marine ecosystem.

– Environmental

• Fish stocks will be comprised of a more natural age/size structure of increased genetic diversity that will make them more robust in the face of changing environmental challenges and less subject to fluctuation caused by alternating strong and weak year classes coming through.

Sharing the Cost of Science and Fisheries Management

Given the experience of most Recreational Sea Anglers, as the abundance of inshore stocks has declined, with some once prevalent species all but disappearing, and the loss from the stock structures of those that remain of fish of a respectable size.

Recreational Sea Anglers could well be described now as ‘Victims of Fisheries Management and Science’.

To suggest that Recreational Sea Anglers should now start to pay towards the cost of that management that has only ever produced decline is preposterous.

And even given a willingness, and a plan, to improve the experience of Recreational Sea Anglers, that has very little chance of meeting its objectives if past experience is anything to go by, asking anglers to pay up front, before it has been demonstrated that any aspirational objectives are to be met, risks greater alienation and bitter ridicule.

However, if measures were put in place and management strategies adopted, with the aim of improving the experience of Recreational Sea Anglers, ie anglers actually catching more and bigger fish as a result of successful directed management, and it was intended to build upon that demonstrable success, then anglers are much more likely to be willing to pay towards the cost of that successful directed management.

But only insofar as all stakeholders who benefit from such science and fisheries management would also be expected to pay proportionately towards those costs.

Closed Areas and Closed Fisheries

Some areas will be closed to harmful activity, there will be ‘closed seasons’ for some species to protect vulnerable seasonal aggregations of feeding and spawning fish, and an increased use of nursery areas to protect developing juvenile fish.

There will be powers to close fisheries at short notice when there are concerns about the level of exploitation, composition of catches etc.

UK Food Security

Our fisheries are an important, essential and irreplaceable part of the UK’s food source.

As environmental change occurs, fisheries, probably more than any other component of our food source, can be detrimentally impacted, especially so if they are allowed to become deteriorated and to lose robustness through exploitation at levels of risk beyond sound and very safe precautionary boundaries.

All involved in fisheries management need to stand back and take stock of the importance of the security of our fish stocks in a changing world, and the implications for present and future generations, if we do not manage and restore our fisheries to be as completely robust as possible.

Getting it wrong, both now in the following decades, risks terrible consequences.

Consequences that we cannot afford, and which nature will not fix for us.